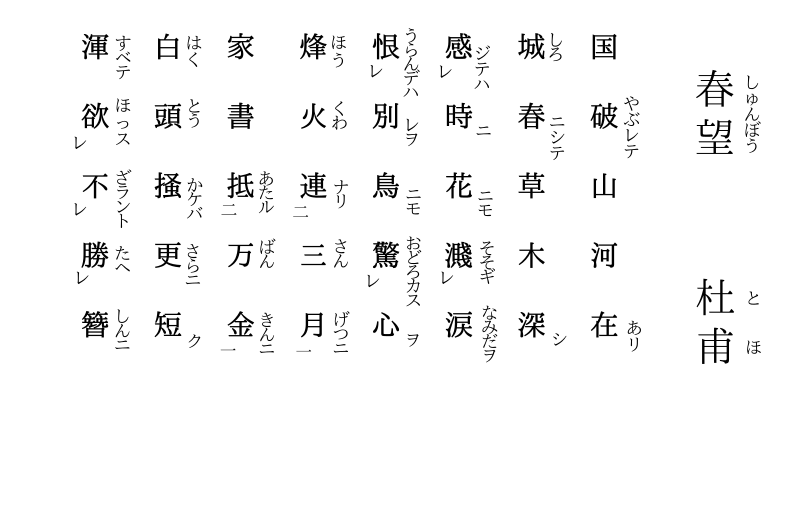

春望 (杜甫)

Michael Wood's In the Footsteps of Du Fu

Du Fu’’s poem “Spring Scene” was written in 757, just months after the collapse of the Tang dynasty during the An Lushan Rebellion. The emperor had fled the capital and so too did Du Fu attempt to flee—only to be captured by the rebels and brought back to the city, where he was held in captivity.

None of this information is contained within the poem itself—nor is it conveyed in the Japanese gloss above.

As I have said, approaching classical Chinese poetry through a Japanese lens can put you much closer to the Chinese original than is normally possible through English translations. This is not least of all because of the shared kanji characters, which convey so much of the meaning—the atmosphere and feeling of the poems. And Japan didn’t just inherit the kanji; for they also borrowed many of the poetic tropes— and so, the strong compression seen in Tang poems can be much easier to unravel or unpack.

Michael Wood, in his wonderful book about Du Fu, makes the point that even for the ancient Chinese, reading poetry was a creative act. The act of reading a Tang poem is much less passive than reading poems with clearly stated pronouns and grammatical inflections. It is highly abbreviated. For example, when I look at a Tang poem, what I see is a series of nouns. But as you can see by the Japanese gloss in kana above, the modern Japanese reader also has to make interpretations— adding verb tense and connective terms. Reading is always a creative act—and Tang poetry is especially challenging (and fun!)

Here is what I see (almost all understandable in Japanese)

country broken/ mountains rivers remain

city springtime/grass trees dense

feel times/flowers shed tears

hate partings/birds startle heart

beacon fires/continue three months

home letters/worth 10,000 taels

white hair/ scratch made shorter

about to/hairclip unable hold

But there are so many questions. Without pronouns, how do we read the second set of couplets? Are the flowers crying because of the (troubled) times or is the poet feeling sad and wondering if the flowers are not also not shedding tears? In Japanese, you don’t need to take a position regarding the pronouns but you do at least have to add verb endings and some conjunctions.

In the above Japanese gloss, the grammar is put in using kana with grammatical verb tenses noted in katakana.

Spring View

The country has fallen, but the mountains and rivers remain

Spring arrives to the capital, trees and grasses grow lush

Feeling these troubled times, the flowers shed tears

Hating these separations, bird startle our hearts

The flames of war continue these three months

Letters from home worth more than 10,000 taels of gold

My gray hair grows thin from worried scratching

Soon there won’t be enough left to hold a hairpin

(I added the words troubled and worried)

In Zong-qi Cai’s fantastic How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology (How to Read Chinese Literature), Cai explains how the poem perfectly captures the four-stage Progression of rising, elaboration, pivot and conclusion.

In Japanese, this is called kishōtenketsu (ki: introduction; sho: development; ten: twist; ketsu: reconciliation).